Authored by: Jitendra Bisht

Edited by: Kausumi Saha

CONTEXT

Section 14A of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2003 mandated the government of India to “compulsorily register every citizen of India and issue national identity card to him” and “maintain a National Register of Indian Citizens” (NRC, hereafter) [1]. Almost two decades after the 2003 amendment to the Citizenship Act of 1955, the abbreviation ‘NRC’ has become a polarising term, evident during the numerous CAA-NRC protests that happened in India starting December 2020. For a section of the country’s population, the process of NRC, in combination with the 2019 amendment to the Citizenship Act, could lead to loss of citizenship and mass detentions, particularly of Muslims in the country. For others, the amendment and the NRC seem to be two separate issues – the former about providing Indian citizenship to non-muslim minorities facing religious persecution in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, and the latter about screening out illegal migrants residing in the country.

This polarisation has been accentuated by the government’s contradictory signals about its plans to implement the NRC process. In its most recent statement in the Lok Sabha in February, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) had clarified that “till now, the government has not made any decision to prepare National Register of Citizens (NRC) at the national level” [2]. However, in an affidavit submitted in the Supreme Court on March 17, the MHA termed the NRC a “necessary exercise for any sovereign country for mere identification of citizens from non-citizens…to identify/detect illegal migrants and thereafter, follow the due process of the law” [3]. Notably, on December 9 2019, the Home Minister himself had told the parliament that “there is no need to create a background for NRC…we are clear that NRC ought to be done in this country, our manifesto is the background…rest assured, NRC is coming” [4]. This was followed by the Prime Minister’s declaration in a public rally in Delhi on December 22 in which he said that there had been no discussion or talk of an NRC for India since his government took power in 2014 [5].

Notwithstanding the divergent and contradictory political narratives on the issue and persisting confusion about the government’s plans, there is a need to understand the challenges inherent in the implementation of such a process. Compulsory registration of citizens would involve establishing or proving one’s citizenship, which has difficulties of its own. Moreover, there is need for a nuanced look at the concept of NRC and its origins to abate the current degree of polarisation around it.

THE NEED FOR NRC

The first NRC in India was prepared for Assam in 1951 based on data from the first census of independent India. The document was prepared in the context of the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act, 1950, which itself came into being in response to the challenge of undocumented migration from East Pakistan into the state [6]. Notably, the Act gave the government the power to “direct such persons or class of persons to remove himself or themselves from Assam” in case “the stay of such person or class of persons in Assam is detrimental to the interests of the general public or any section thereof or of any Scheduled Tribe in Assam” [7]. One can infer that the intent of the Act and the subsequent NRC was to protect indigenous identities, particularly of Scheduled Tribes, from the influx of migrants coming from violence-hit East Pakistan. After the expulsion of such migrants under the Act, the NRC was completed listing the permanent residents of the state. This NRC was updated and released in the public domain in August 2019 after a number of Supreme Court orders in 2013 and 2014 to the Central and State governments [8].

The idea of a nationwide NRC also took shape within the policy discourse of undocumented or illegal migration, albeit with an aim to strengthen national security. In April 2000, based on the recommendations of the Kargil Review Committee, a Group of Ministers (GoM) led by the then Home Minister L K Advani was constituted to review India’s “National Security system in its entirety” [9]. One of the aspects that the GoM reviewed was Border Management, as part of which it had identified illegal immigration as a key challenge. To quote the GoM report published in 2001,

“We have yet to fully wake up to the implications of the unchecked immigration for the national security (sic). Today, we have about 15 million Bangladeshis, 2.2 million Nepalese, 70,000 Sri Lankan Tamils and about one lakh Tibetan migrants living in India. Demographic changes have been brought about in the border belts of West Bengal, several districts in Bihar, Assam, Tripura and Meghalaya as a result of large-scale illegal migration. Even States like Delhi, Maharashtra and Rajasthan have been affected…The massive illegal immigration poses a grave danger to our security, social harmony and economic well being” [10].

As an effective response to this purported threat to national security, the GoM had suggested “compulsory registration of citizens and non-citizens living in India to facilitate preparation of a national register of citizens” [11]. This was to be followed by issuance of Multi-purpose National Identity Cards (MNIC) to all citizens and cards of a different colour and design to non-citizens. The GoM also suggested that a law be enacted for the same as it would help the preparation of the NRC. Consequently, required amendments were made to the Citizenship Act 1955 in 2003 to give the central government the mandate to carry out the NRC exercise.

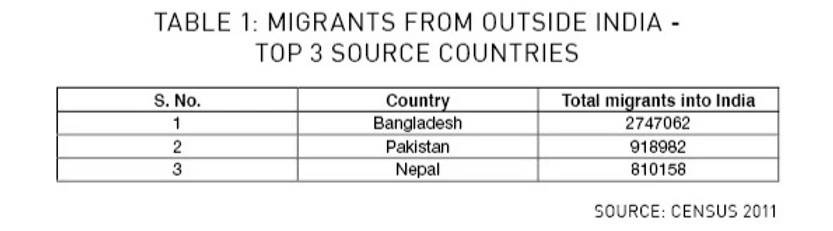

Whether the danger to security, social harmony and economic well being as identified by the GoM was based in reality is a pertinent question here. According to the 2001 Census, there were a total of 6,166,930 (over 6 million) migrants [12] from other countries in India, less than half of the number quoted by the GoM report just for people from Bangladesh [13]. As per Census 2011, the total number of migrants from other countries had come down to 5,363,099 (0.4% of India’s population) registering a decline of over 8 lakh people in absolute numbers [14]. Table 1 shows Census 2011 data on the top 3 countries from where migrants have come into India and it is clear that their numbers are quite low compared to the ones quoted in the GoM report. Though available data is not the only parameter to judge the consequences of illegal immigration to national security, it certainly forces one to question the magnitude of the issue presented in the GoM report.

THE DIFFICULTIES IN IDENTIFYING CITIZENS AND NON-CITIZENS

The NRC, in simple terms, is a process of establishing citizenship that will help the government screen out illegal migrants. After the enactment of the 2003 Amendment to the Citizenship Act, the government laid down the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules the same year. The Rules lay out the various stages and actors involved in the process of preparing the NRC. Some of the most important aspects of the process as per the Rules are as follows:

- The Registrar General of India shall function as the Registrar General of Citizen Registration and shall establish and maintain the NRC.

- The NRC is to be divided into its sub-parts, namely, the State Register of Indian Citizens, the District Register of Indian Citizens, the Sub-district Register of Indian Citizens, and the Local Register of Indian Citizens (LRIC) containing details specified by the Central government.

- The government may decide the date for the preparation of the Population Register which shall be compiled using data regarding usual residents under the jurisdiction of the Local Registrar.

- The LRIC shall contain details of persons after verification from the Population Register.

- The Central Government shall carry out a house-to-house enumeration of each family and individual residing in a local area including their citizenship status.

The Rules clearly put the onus of proving citizenship upon the citizens, failing which their names could be removed from the NRC, “thereby affecting the Citizenship status of the person” [15].

BUT HOW DIFFICULT IS IT TO ESTABLISH CITIZENSHIP OF AN INDIVIDUAL?

To answer this question, and “to understand the complexities involved along with technical specifications and technology required for national roll out” of a register of citizens, the Ministry of Home Affairs launched a pilot MNIC project in October 2006 [16]. The project was held across 12 states and one Union territory – Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Delhi, Goa, Gujarat, Jammu and Kashmir, Rajasthan, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, and Puducherry. It covered a total population of 30.96 lakh. As part of the project, persons who could prove their citizenship were to receive unique National Identity Numbers and Identity (smart) cards. At the end of the final maintenance and updating phase of the project in March 2009, roughly 12 lakh people were issued identity cards. That means the government could verify the citizenship of only 12 lakh individuals, or in other words only 40% of the people were able to prove their citizenship. In a submission made to the Standing Committee on Home Affairs in Rajya Sabha in 2007, among the reasons listed for the delay in implementation and poor success rate of the project were:

- The very cumbersome and tedious process of verification of citizenship; individuals were not found at their place of residence.

- Weak document base for determining citizenship of individuals in rural areas, specially for agricultural labourers, landless labourers, married women, etc. [17].

Additionally, as per the subsequent Annual Report of the MHA, “the experience of the pilot has shown that determination of citizenship is an involved and complicated matter” [18]. Considering that the results of this pilot are the only available instance of a nationwide process of ascertaining citizenship till now, one can imagine the difficulties the authorities may encounter when such a process is scaled up to include all citizens of India. Moreover, as the success rate of the pilot indicates, the number of people who fail to prove their citizenship could be much higher.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In principle, there is no denying that every sovereign country in the world has the right to undertake the taxing process of identifying citizens and non-citizens, for the purpose of identifying illegal migrants, among others. For a country of 1.3 billion people with conventionally porous borders and a neighbourhood replete with a variety of security challenges, this task becomes even more important. However, the policy discourse within which the government’s push for a nationwide NRC took birth during the early 2000s was based on unverified data, to say the least. This certainly raises concerns on the rationale of the process itself. Also, as stated earlier, migrants from outside India constitute a share of roughly 0.4% of India’s total population as per the 2011 Census. In this context, the government needs to justify putting its resources and citizenry under stress to identify such a small share of the population. The possible economic burden of a nationwide NRC on the state as well as citizens, based on the costs incurred during the recent updating of the Assam NRC, has already been discussed at length by many policy experts [19] [20] [21] [22]. Additionally, as the experience from the MNIC pilot project has shown, establishing citizenship is a complicated task, particularly so with the weak document base in the vast rural landscape of the country. Taking into account the above discussion, one may conclude that the NRC, whatever the government’s current plans may be regarding its implementation, begs a reappraisal from policymakers.

ENDNOTES

[1] https://indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/4210/1/Citizenship_Act_1955.pdf [2] https://mha.gov.in/MHA1/Par2017/pdfs/par2020-pdfs/ls-04022020/LS%2022.pdf [3] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/nation-needs-nrc-centre-tells-supreme-court/article31101913.ece [4] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/nrc-aane-wala-hai-amit-shah-makes-his-intention-clear/videoshow/72454609.cms [5] https://www.indiatoday.in/india/video/congress-urban-naxals-spreading-lies-about-nrc-pm-modi-1630577-2019-12-22 [6] https://thewire.in/rights/nrc-assam-accord-updating-residents [7] https://indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1674/1/A1950-10.pdf [8] http://www.nrcassam.nic.in/pdf/17%20Dec%202014%20Record%20Of%20Proceedings_SUPREME%20COURT.pdf [9] https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/GoM%20Report%20on%20 [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] https://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/migrations.aspx [13] http://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/d-series/D-1/DS-0000-D01-MDDS.XLSX [14] Migrants by place of birth, which gives a picture of lifetime migration, is important in this regard to gauge the number of people who have come from outside the country. [15] https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-Act&Rules/notifications/citizenship_rules2003.pdf [16] https://mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/AR%28E%290809.pdf [17] http://164.100.47.5/rs/book2/reports/home_aff/124threport.htm [18] https://mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/AR%28E%290809.pdf [19] https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/caa-and-nrc-these-two-pose-a-serious-threat-to-indias-development-story-muslims-religious-fundamentalism-secular-amit-shah/story/392319.html [20] https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/nrcs-cost-benefit-analysis-caa-protests-6197030/ [21] http://www.rightsrisks.org/press-release/the-economic-cost-of-draft-nrc-poor-made-extremely-poor/ [22] https://theprint.in/opinion/why-india-doesnt-need-nrc/324771/